En exclusivité pour Regard au Pluriel

Richard Wilson

Interview // Rajesh Punj // May 2014

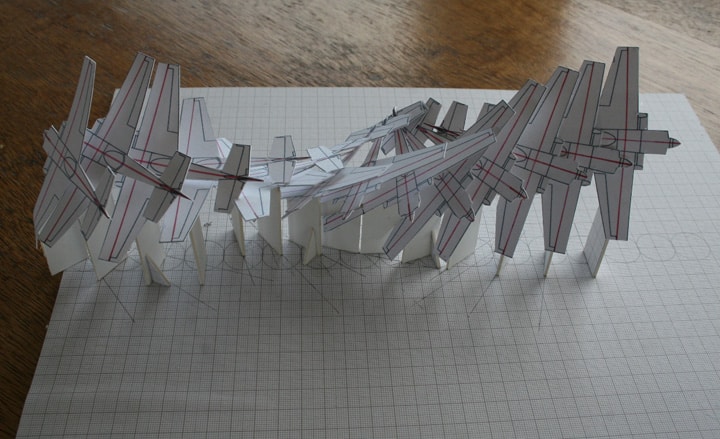

Richard Wilson with Slipstream models © LHR Airports Limited

Richard Wilson with Slipstream models © LHR Airports Limited

Acting Alone

Slipstream is one of Richard Wilson’s most innovative projects to date. Originally based on the induced motion of a car rolling over, translated into the aeronautical endeavour of a small propeller plane turning through the air at high altitude; Wilson’s elevated aluminium clad sculpture, twists through the central space of the redesigned new terminal building like an elongated spacecraft settling for earth. And as the motive for our meeting, this titanic sculpture serves to facilitate what is a remarkably candid conversation about his original appetite for the grandiose scale of American sculpture, and of its influence upon his more substantial interventionist works. His indicative need for a ‘wow’ factor when drawing an audience in, and of his wish to redress the notion that his works are in any way acts of ‘vandalism’. Throughout Wilson advocates for more rudimentary principles, referring to ‘honesty’ and ‘integrity’, ideals that he argues are slipping away from a lot of leading artist’s practices now, in favour of more commercial interests. All of which makes Wilson a sculptor in the purist sense.

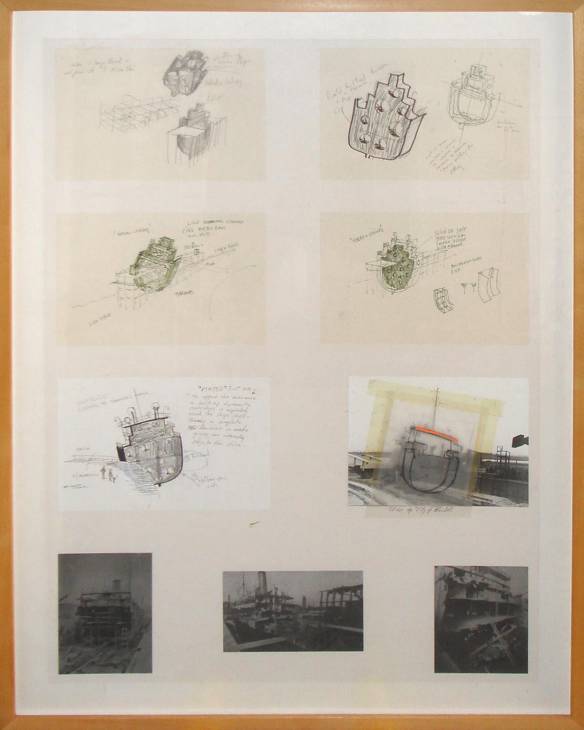

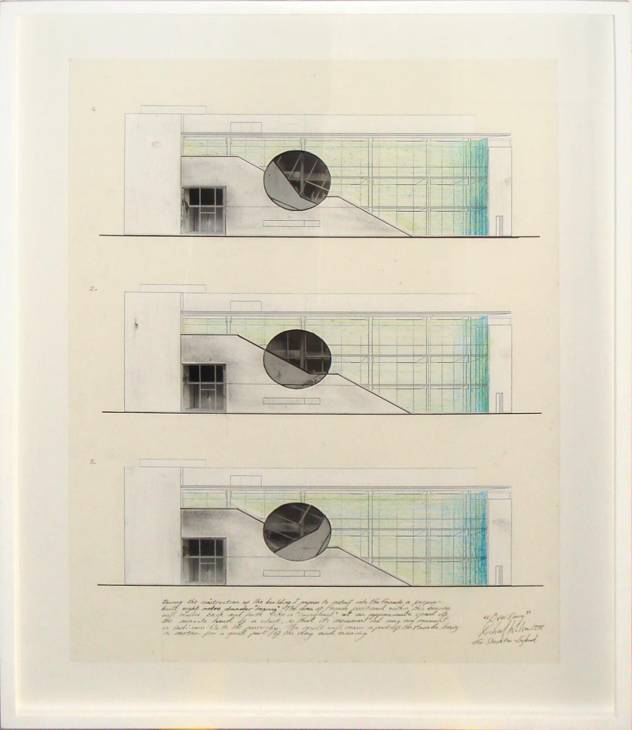

Early drawing for slipstream by Richard Wilson

Early drawing for slipstream by Richard Wilson

Rajesh Punj: Possibly we should begin by your explaining and exploring the significance of your new work, ‘Slipstream’, and of how important the scale of this work is?

Richard Wilson: It’s an interesting question relating to scale, because first of all the obvious question people will say is it’s ginormous, why? And you have got to understand I have spent a good part of my professional career as a sculptor; dabbling with architecture, playing with architecture, undoing it, and therefore I’ve had to take on that scale. Therefore if you have an idea about spinning a facade, you don’t do it as a six foot piece. A facade is looking at the extremities and thinking what will the budget allow for? So obviously architecture is a dedicator for scale, and the other thing is the canvas that I was given, which is the empty void of the covered court area. Which is supported in the middle by eleven columns, and in relation to the brief that I was given, was that the sculpture could only be supported off of the columns. So I have only used four of them, and I have probably used just over a third of the supports for the ceiling.

So in that respect it’s not a very big sculpture; but it is big when you see it. And it’s to do with human scale, non-human scale, and architectural scale. So I’ve worked with the scale of the room, and I’ve worked with the scale of the interior of the architecture. It’s not as big as the building; it’s only in one third of the building. You have got the car-park arrivals area from London, and then you have the covered court area, and you have the terminal. So I have got the middle piece; and I’ve taken four of the eleven columns of the middle piece, therefore it’s not a sprawling work that occupies three parts of the architecture, it only occupies one part of it. So in that respect I think it is right for where it is, and the size is right for where it is located.

And in terms of the visual people like to see exciting things, dramatic things, and things that are going to arouse them, and dazzle them in some way, and startle their imaginations, and I think I work on that level. It’s a little rude in the sculpture world, but I use it, and I suppose I use it because I am working a lot of the time in an environment where my audience isn’t well versed in an art grammar. Here we are at an airport where 20 million people a year come through this terminal, then they are not all going be au fait with the visual arts; they (the audience), have not had the training I have had, so I have to use something that gets that wow factor going.

RP: You appear to consider the external factors of a work, (the volume of space you begin with, and your wish for the work not to overwhelm that setting in any way), as much as the work itself; am I correct in thinking that?

RW: I think that’s true, and I think that one learns to be very sensitive, and that comes through various reasons. And it is something I have had to really think about, and work with over the years, because I spoke about the idea that you can make constructions and build, which is what this is. Or as a lot of my work in the pass has done, which is to unravel and undo, and look inside of architecture. When you do that, you tend you get critics talking about the artist as being a vandal, that I am attacking architecture, and disagreeing with the architect; and it’s not that at all. Because they are sensitively choreographed pieces; so when you do turn the facade of a building, or plant a sculpture in the floor of a gallery, or take a window and bring it into the space to adjust the architecture, it’s all incredibly thought out and sensitively worked. I wouldn’t say hundreds, but there are lots and lots of drawings, sketches and models made, to get it to sit properly and right in the space. It’s not an attack, it’s not an act of vandalism. I’m not the mad axe man coming in to attack architecture, as has been written about me. So I have had to think about it.

RP: That comes across as a strange accusation, for someone so deliberate in everything that they do. Are you?

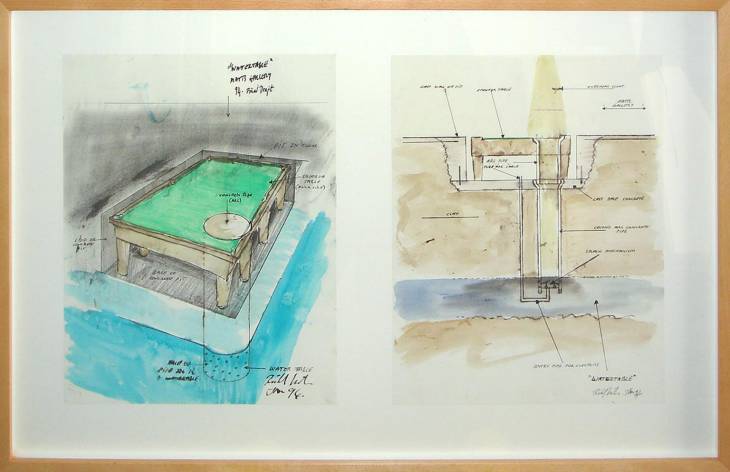

RW: I can understand it, because what it is, is that often people don’t know the hidden agenda, and I am referring again to these pieces I have just mentioned, (Over Easy 1998, The Arc, Stockton-Upon-Tees; Turning the Place Over 2008, Liverpool; Water Table 1994, Matt’s Gallery, London), when you know you have been given permission to undo a window, and you have a very good understanding of how that window operates, as in She Came in through the Bathroom Window 1989; I could just unbolt it, bring it back in, and put it back up afterwards. I knew with Turning the Place Over 2008, I could do a pastry cut in the building, mount that onto a spindle and spin it, because the building was going to be pulled down afterwards; so those were the hidden agendas, given that information. The same with the Serpentine Gallery, Jamming Gears exhibition, in 1996; they, (the gallery), were going to excavate their basement out. And they had been given lottery money to put an education room down there. Therefore I could dig the floor, because when I’d gone it was all coming up anyway. So there was an understanding that I would use the parameters of what was allowed and doable; and in that respect I probably challenge the architecture in that way. Where as in the museum environment, it is one where the architecture is sacrosanct, you can’t put a nail in the wall, you can’t undo that floorboard; you know it is difficult enough taking a light bulb out, there are so many health and safety restrictions. So I research all of those things, and just basically determine what the available parameters are, and then work out what I can do within the parameters as I understand them. It is not vandalism, it’s not that I go in and don’t ask, or seek permission, and just assume I can do these things.

RP: How integral is drawing when planning a work?

RW: Drawings are vital for me, because number one I am working with teams, and I have got to be able to express my idea sensibly, and in a coherent way, so that there is no misunderstanding. Sometimes I am invited to make drawings and models to assist in the securing of funding, so you would be asked to make a maquette in order to convince someone who is not that well versed in the art grammar, that they can say oh I get it, I like it, let’s put money forward into that, so it will be a local authority perhaps.

So these things are done to the best of my ability, in order to convey the best possible way the concept as it is at that moment in time. The other thing the drawings are done for is, in the same way people go to the gym to work-out, I use drawing as a mental limbering up. I have got to get very familiar with my work, because once I am familiar with it, it is handed over. Made in Hull, (referring to the slipstream sculpture), and assembled here. It’s not done in the studio where you get time to look and duel upon it and change things, you have got to get it right, like the architect’s got to get it right. And you can’t be seen to be wasting money; you can’t say actually I don’t like the middle, can we get rid of that and do it again, because you look unprofessional, and you are throwing money away at that point.

RP: There must be a point with certain projects then when you are having to be much less attached to a work, as with Slipstream. Where you are less able to come back to something, and have the opportunity to amend it whilst it is under construction. How do you operate under those circumstances?

RW: With Slipstream, and any of the other major works where the sculpture is rooted in a building outside a big gallery idea, it requires of me to work like an architect; that is you work, and work, and work on the idea, to get it fine-tuned to what you consider is correct, and then you hand it over to the engineers, and onto the manufacturers; and at that point you don’t lose control on it, but you obviously can’t chop and change it after that. And when a project like this takes three years, you most intensive period is probably the first six months, at the very beginning. After that you are following it, signing bits off, saying I don’t like the way those bits work, or can we just clean that there, or I don’t like that bit there, but essentially you can’t challenge your own aesthetic. You can’t say I don’t like the way I have made that work, can I get rid of all of that.

RP: There is something almost contradictory about your lexicon for public sculpture; when you talk of inevitable ‘compromises’, and of your wish for ‘being sympathetic’ to a space; in relation to the artist as ‘actionist’. Are the two mutually exclusive?

RW: It comes with age, you start to realise that sometimes you can be a bit belligerent, and you think the idea is right; and you have tried and tested it on your models and drawings, and then someone will come along and say it can’t be that high, it’s got to drop down a bit so you can see the exist sign, and you drop it, and you think actually I am glad that surfaced because it could have been a bold, brisk attempt at saying, here I am, flying up and away, when in fact there is a subtly aswell, when you reduce and do those things. Sometimes fortuitously it’s a blessing in disguise, and you rarely say I am glad that went that way, because I had got it wrong; you keep quiet about it, and you pretend it was always intended. But obviously artists have to work in that way all the time. I think everyone has to give and take in that situation. The building has to give a bit, but the sculpture has to give a bit back aswell.

RP: You have referred to the significance of scale in your work; how important was American sculpture to you, as an influence?

RW: I really used the library, and I became very involved in the American artists at art college. Very involved in Land Art, and I become very involved with scale. (Richard) Serra, Mark di Suvero, and some of the other big land artists, Walter de Maria, Michael Heizer among them. And I came to Gordon Matta Clark very late, after college. But that kind of bravado, the idea that scale and the very American idea that rather than use the path you know, get off the path and make your own trail. That idea that you have something to say, say it; and don’t follow the conservative trend, break away and be your own person; be your own ideas. And I always thought there was something wrong, that if anyone was making work like you that that was wrong; and for me it was about being unique.

Rajesh Punj, May 2014

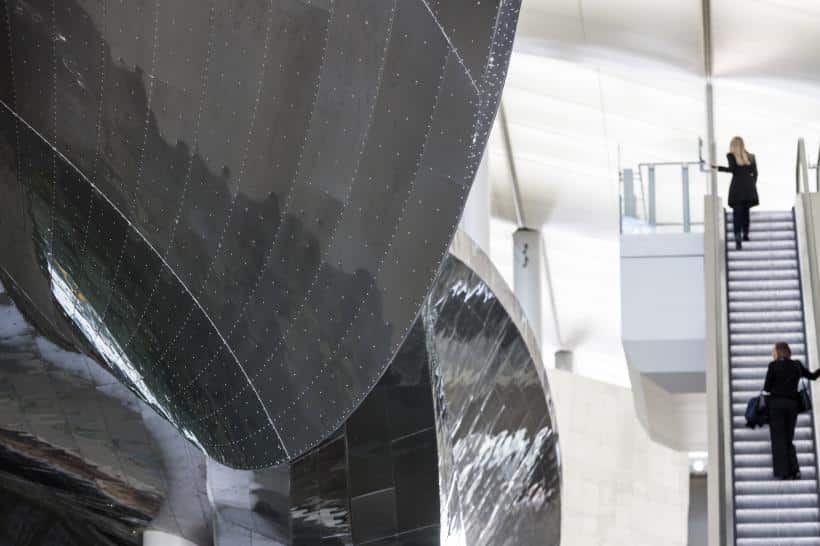

Slipstream

“This work is a metaphor for travel,” says Wilson of the design. “It is a journey from A to B, where sensations of velocity, acceleration and de-acceleration follow us at every undulation.”

TERMINAL 2 HEATHROW AIRPORT, 2014

Heathrow Airport in 2011 unveiled plans for an ambitious and stunning sculpture commissioned from sculptor Richard Wilson R.A for the new £2.2bn Terminal 2.

Titled ‘Slipstream’, the 80 metre long sculpture is installed outside the terminal in the covered court area. All arriving and departing passengers will pass through the court and be able to view what will become a landmark sculpture for London.

Slipstream is inspired by the exhilarating potential of flight, coupled with the physical aesthetics of aircraft. Constructed in aluminium, the piece aimed to solidify the twisting velocity of a stunt plane manoeuvring through the volume of the new terminal.

Richard Wilson // Slipstream // Photographer David Levene

Richard Wilson // Slipstream // Photographer David Levene

Richard Wilson // Slipstream // Photographer David Levene

Richard Wilson // Slipstream // Photographer David Levene

Drawings by Richard Wilson

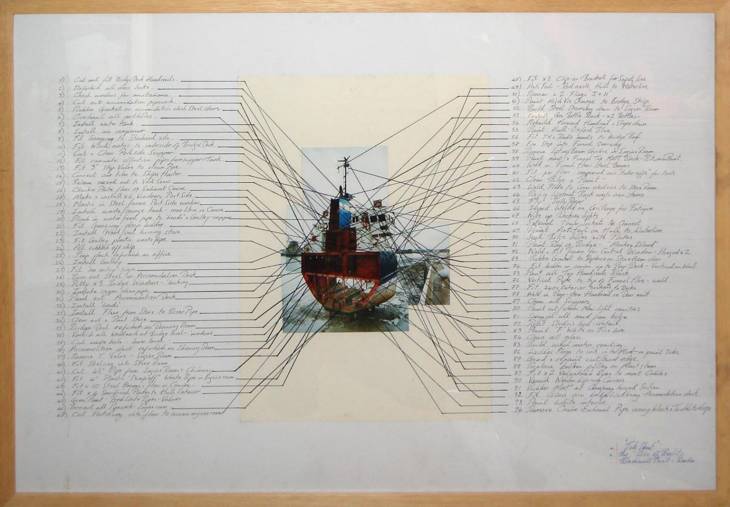

Slice of Reality / 2000 / © Richard Wilson /Tate London

Slice of Reality / 2000 / © Richard Wilson /Tate London

Over Easy / 1998 / © Richard Wilson / Tate London

Over Easy / 1998 / © Richard Wilson / Tate London

Watertable / 1994 / © Richard Wilson / Tate London

Watertable / 1994 / © Richard Wilson / Tate London

Slice of Reality / 2000/ © Richard Wilson/ Tate London

Slice of Reality / 2000/ © Richard Wilson/ Tate London

Richard Wilson // website